Blog by Sona Avetisian, student on the MA in Victorian Literature, Art and Culture

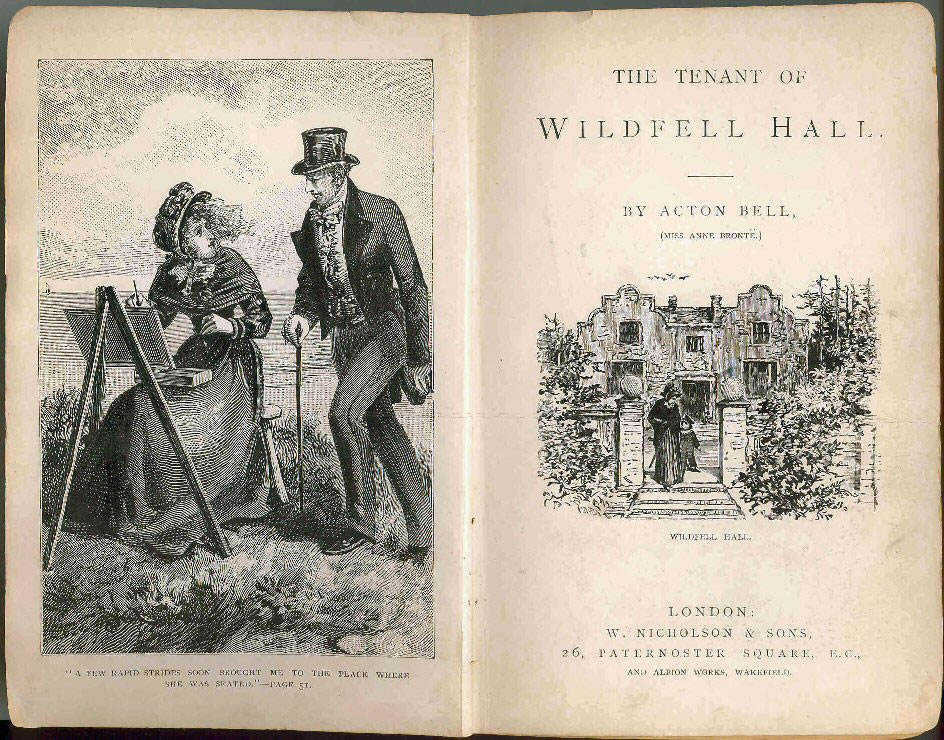

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall

Ecofeminism is a philosophical framework that explores the interdependence of gender oppression and environmental degradation, arguing that patriarchal systems of dominance exploit both women and nature.1 In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1948), Anne Brontë engages with themes of gender, patriarchy, and nature to critique Victorian society. Within this framework, ecofeminist theorists such as Elizabeth Dodson Gray, in her Green Paradise Lost (1981), develop the idea of the "feminisation of nature", emphasising how the natural world is associated with feminine attributes and subjected to masculine authority".

Many feminists have been critical of ecofeminism for the way that it considers an unequal relationship between women and the environment, portraying women as passive "earth mothers" or reproductive creatures. While this criticism has some logic, another viewpoint requires consideration. Women's relationship with nature should be viewed as a powerful link that builds resilience and empowerment rather than a weakness. Anne Brontë, for example, uses this relationship in her novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) to reject Victorian society and escape patriarchy.

Feminist researcher Elizabeth Dodson Gray, in her Green Paradise Lost (1981), believes that men's urge to rule women and the environment derives from sexual inequalities in gender development.2 She argues that male newborns reject their dependence on women, leading to long-term psychosexual ramifications for how males interact with women and the feminine3. This reinforces a patriarchal mindset that regards women as inferior and dependent - a mindset which Gray critiques and rejects.4 Notwithstanding Gray's dissatisfaction towards this patriarchal construct, she does not promote female superiority. She advocates for balancing maternal and paternal responsibilities5.

The title character of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, Helen Graham, lacks the characteristics of an ideal wife according to Victorian patriarchy. She escapes an abusive marriage and now lives independently with her son, Arthur. When Helen arrives at Wildfell Hall, she faces challenges rooted in her ambiguous status as a "widowed" woman. Societal suspicion and gossip are some of the difficulties that patriarchal expectations impose on women's dependence on male support.

Priti Joshi's Masculinity and Gossip in Anne Brontë's The Tenant (2009) explores the novel's critique of Victorian masculinity and emotional repression. Joshi contends that Brontë's representation of masculinity highlights the negative impact of hyper-rational ideas and emotional suppression in patriarchal societies. Joshi specifically investigates Gilbert Markham's early mistrust of Helen based on society's rumour and his reliance on visual "proof" rather than Helen's words.6 In Chapter 15, when Gilbert sees Helen and Mr Lawrence walking together, he immediately jumps to conclusions based on appearances (he sees them together, and the first thing that crosses his mind is that Helen and Mr Lawrence are secret lovers. However, in reality, he is her brother).

Helen says: "Why did you not come to hear my explanation on the day I appointed to give it?"7 Gilbert responds: "Because I happened, in the interim, to learn all you would have told me—and a trifle more, I imagine."8 This interaction shows that Gilbert trusts his eyes rather than asking Helen directly.

Helen is not the only victim of patriarchal abuse. Her friend, Milicent Hargrave, is also abused by her husband, Ralph Hattersley. In the book, she represents the woman society wants to see constantly tamed. Compared to Helen, she never manages to stand up for herself, considering herself weak. However, she knows such an attitude towards herself is wrong and unjustified. In chapter 32, Milicent and Helen discuss Esther, Milicent's sister. Helen says:

"I wish you would seriously impress it upon her, never, on any account, or for any body's persuasion, to marry for the sake of money, or rank, or establishment, or earthly thing, but true affection and well-grounded esteem".

"There is no necessity for that," said I: "for we have had some discourse on that subject already, and I assure you her ideas of love and matrimony are as romantic as any one could desire".

"But romantic notions will not do: I want her to have true notions".9

Both women recognise the mistakes they have made and wish Esther to stay away and not get married unless she feels that the partner of her choice is capable of being a good husband and father who would respect her and make her feel safe around him. Anne Brontë had an unclouded vision of what marriage looked like in Victorian England, and through the characters of Helen and Millicent, she stood up against it.

Probably the most significant connection of a human with nature that the reader can see starts with Helen moving to Wildfell Hall. The house was abandoned for years, and no one could take care of that place for a long time. It belongs to her brother Frederick Lawrence, who allows her to stay there as a refuge. The house, at first, looks quite derelict. Wildfell Hall has a Gothic appearance with broken windows and dilapidated roofs. Once clipped into decorative shapes, the hedges in front have sprouted into strange forms with a "goblinish appearance".10 Rather than romanticizing rural life, Brontë reveals Helen's harsh realities. Helen discusses the isolation and loneliness she feels at Wildfell Hall, seeing it as a 'dreary wilderness' that echoes her emotional and social isolation throughout her marriage. The reader can see how depressive the life around Wildfell Hall was when Gilbert Markham describes it in chapter 2:

I left the more frequented regions, the wooded valleys, the corn-fields, and the meadow-lands, and proceeded to mount the steep acclivity of Wildfell ... where, as you ascend, the hedges, as well as the trees, become scanty and stunted, the former, at length, giving place to rough stone fences, partly greened over with ivy and moss... The fields, being rough and stony, and wholly unfit for the plough, were mostly devoted to the pasturing of sheep and cattle; the soil was thin and poor: bits of grey rock here and there peeped out from the grassy hillocks; bilberry-plants and heather—relics of more savage wildness—grew under the walls; and in many of the enclosures, ragweeds and rushes usurped supremacy over the scanty herbage; but these were not my property.11

Beyond the depressing surroundings of Wildfell Hall, which represent a dark period in Helen's life, her work becomes an important source of escape and freedom from oppression. Helen regularly escapes her difficult marriage by painting landscapes, trees, and flowers. These images show her great love of nature, give her peace and represent a symbolic and tangible act of resistance against her captivity. Helen's painting expresses her longing for autonomy and freedom, briefly liberating her from both the confines of her marriage and the restrictive expectations set by Victorian society. As proof of this, we can look at the description of one of Helen's paintings by the narrator:

"It was a view of Wildfell Hall, as seen in the early morning from the field below, rising in dark relief against a sky of clear silvery blue, with a few red streaks on the horizon, faithfully drawn and coloured, and very elegantly and artistically handled.

"I see your heart is in your work, Mrs. Graham…"12

The description of Wildfell Hall illustrates Helen's love of nature and her ability to find peace in it. As previously noted, ecofeminism stresses women's strong connection to nature, frequently portrayed as a source of resilience and empowerment in the face of patriarchal tyranny.

The feminization of nature highlights ways in which women and the natural world have been neglected and exploited by systems of patriarchy. However, it can also allow for resistance, empowerment, and unity as women recover their agency and reconnect with nature.

Sona Avetisian came to the UK in 2023 and earned an MA in English Literature in 2024. Two of her modules emphasised Victorian literature, and her dissertation is on Religious Critique and Gender Advocacy in Anne Brontë's novels. Coming from Armenia, where patriarchal traditions are still firmly established, she found Brontë's portrayal of patriarchal brutality and women's struggles to be strikingly relevant.

Bibliography:

Bronte, Anne. 1993. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks)

Duthie, Enid L. 1986. The Brontës and Nature, 1st edn (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan)

Gray, E. D. 1981. Green Paradise Lost (Roundtable Press)

Han, Catherine Paula. 2017. "The Myth of Anne Brontë," Brontë Studies, 42.1: 48–59 https://doi.org/10.1080/14748932.2017.1242646

Joshi, Priti. 2009. "Masculinity and Gossip in Anne Brontë's Tenant," SEL Studies in English Literature 1500-1900, 49.4: 907–24 https://doi.org/10.1353/sel.0.0079

Miles, K. 2024. ‘Ecofeminism’, Encyclopedia Britannica.