Kate Devine is in her fourth year of part-time PhD study. She is writing her thesis on the expressions of craft in Italian avant-garde art and design from the 1960s and 1970s. She also works as a guide for the National Gallery in London, and in this blog she reflects on the pros and cons of the recent move to online programming at museums and galleries.

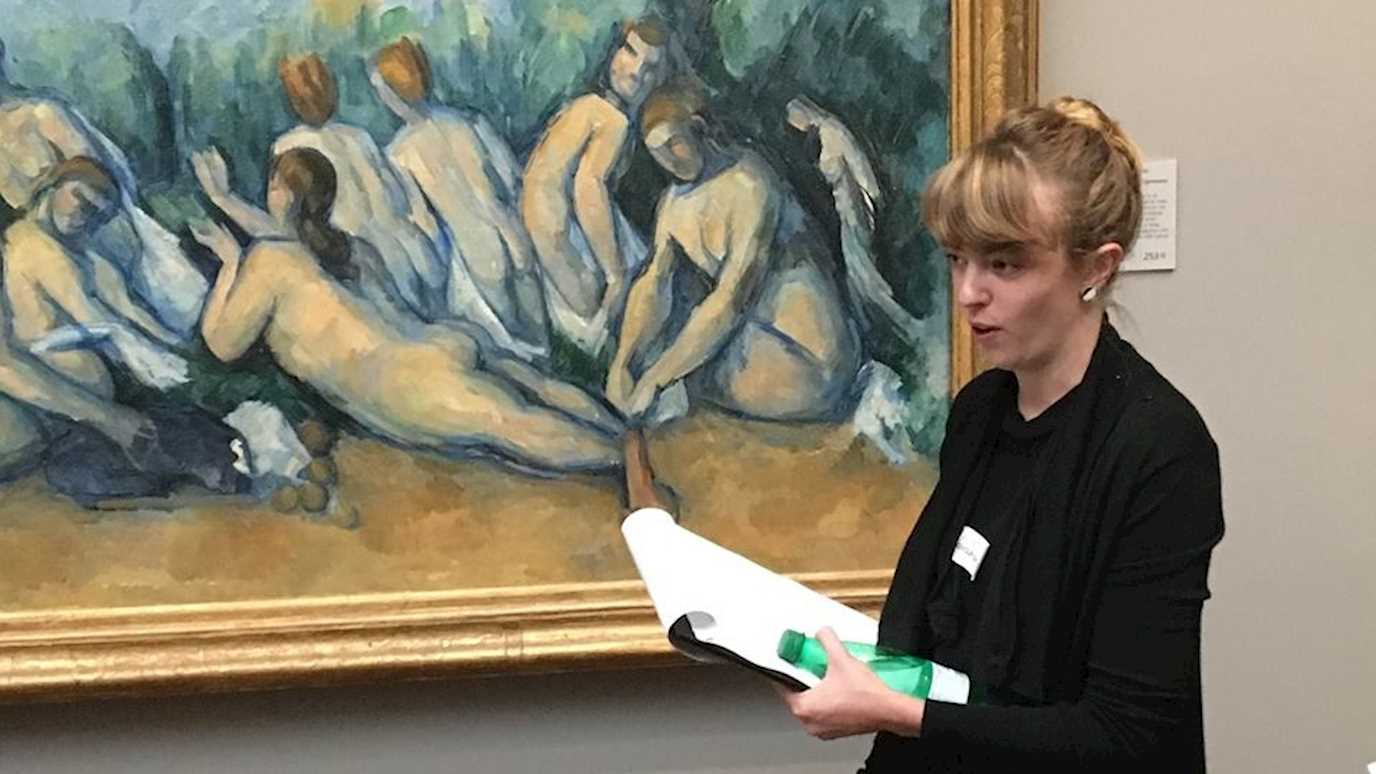

Kate Devine at work at the National Gallery

Many of us have missed visiting museums and galleries over the last six months, and even though we are gradually gaining entry again to much-awaited exhibitions and familiar collections, the experience today is somewhat different to what we were used to.

During the pandemic, museums have been forced into a period of reflection. Unable to connect with their audiences in the usual way, onsite and in person, they have had to think about what a museum can be when it is no longer a physical place to see art and objects. Some have offered virtual exhibition tours, even enlisting the help of robots in the case of Hastings Contemporary! While others have turned to world class social media output, in the case of the Royal Academy of Arts (well worth a look).

Even when audiences have been allowed to return, they look quite different from before. At the National Gallery for example, my role usually involves onsite visitor engagement -- from taking school groups around the galleries, to public guided tours and lectures. Apart from the schools, a large number of my audience, and of visitors overall, are usually tourists. Today that number has fallen dramatically, and we are seeing a smaller, more local audience in the galleries. On the flipside, while onsite visitors may be mostly UK-based, the move to online public engagement has seen us reach many more people across the world, virtually.

Public engagement programmes -- that is, the events, youth schemes, tours, etc. that go alongside the basic visitor experience -- are yet to re-start at most arts institutions and museums. The difficulty of social distancing in a guided tour group, lecture theatre, or art workshop has meant that many organisations have stopped these events completely, while others have moved the enterprise entirely online.

The upshot of this wholesale move to online programming has been a quick change of internal hierarchies. Where digital departments may have been seen in a supporting role, they are suddenly the most in-demand and crucial people in the organisation. There are rarely enough of them to go around, and it has taken time to develop new systems to share out their skills across the departments that need them. Never has the term ‘human resources’ seemed more appropriate! While some of these new digital endeavours will last only for the duration of the pandemic, others I believe are likely to become part of a more integrated approach to public programming into the future.

One example of a successful revenue-producing offer is ‘Stories of Art’, the National Gallery’s annual art history survey course. The format of the course has for years been a weekly two-hour lecture in the Sainsbury Wing theatre, followed by an optional gallery tour relating to the lecture. The course would usually have a capacity of 328 seats but this year it has moved online, and though there has been a reduction in price, the number of participants has risen to around 700, having a very real and needed impact on the department’s finances.

Another key element of the National Gallery’s public engagement were the visits of school children from all over the country and abroad. Whether welcomed or not by the gallery’s visiting public, school groups have long been a huge part of the national institution’s programming, with hundreds coming to visit the site every week of the school year. These visits too have been moved to the virtual classroom with guides like me visiting schools by way of Zoom. Though nothing can replace the excitement of a real trip, techniques such as guided visualisations, soundscapes and 360 views of the gallery space can be used to give a sense of leaving the classroom even if it’s not possible in reality.

Moving these sessions online will allow us to reach out to schools who would not ordinarily come to the physical site, either because of the distance involved or the difficulty of organising trips (for example, with SEND (special educational needs and disabilities) schools or pupil referral units). Though the priority is certainly to reach pupils in the UK, we have already had requests for sessions from as far afield as South East Asia -- tackling the time difference will be interesting!

All of these schemes, of course, do rely heavily on access to technology and reliable internet connection. Something that has been brought to light during the course of this lockdown is precisely how uneven that access is throughout the country. There are audiences for whom the digital move will limit or completely remove their access to museums and galleries. For example, a pioneering monthly art club at the Royal Academy of Arts has, for years, invited service-users of several homelessness charities to come to the gallery. Many of the people who would usually come to this event do not have reliable access to smartphones and computers with the internet. The same can be the case when thinking about older audience members who might not be as familiar with the technology needed, as well as the difficulty of reaching D/deaf or blind and partially sighted people, or those with dementia -- all audiences for whom there used to be regular onsite programming at our major museums and galleries.

So there are certainly pros and cons to moving online. In a post-Covid future (assuming our institutions survive the crisis, which is another question) we can look forward to a blended offer from our national museums and galleries, the opportunity to be onsite when it matters, while also having many more chances to engage with these institutions from the comfort of our own sofas (or classrooms).